Note: This is a repost of a piece from the principles series that I published last year. I’m making slow but steady progress on some formal analyses and models which build on these informal explorations. I look forward to sharing this work soon, likely early in 2025.

The eighth principle of systems science states that systems use governance subsystems to achieve stability.

Governance is the process that systems use to regulate their long-term behaviors. Systems use governance subsystems to maintain their internal functioning and ensure they can sustain their existence over time.

This post will examine the role of governance within cryptoeconomic systems. Since the point of a blockchain is to provide a ledger of universally accepted truth, well-functioning governance is an essential aspect of maintaining the integrity of these complex systems.

We will look at three public blockchains with very different approaches to governance: Bitcoin, Ethereum and Cosmos Hub. Examining governance crises faced by each system will help us understand the strengths and weaknesses of their governance processes.

Off-chain and On-chain Governance

Off-chain governance refers to a process in which decisions about changing the rules of a blockchain are made through an informal process of social discussion. If the decisions are approved, they are implemented in code.

On-chain governance is a process in which decisions about changing the rules of a blockchain are decided by a formal stakeholder vote. Users who hold a token with governance rights vote directly on the blockchain.

Bitcoin users who hold bitcoin (BTC) and Ethereum users who hold ether (ETH) can’t use their tokens to vote on changing the rules of the underlying blockchains. Cosmos Hub users who hold the ATOM token can.

Bitcoin’s apolitical Governance

Subsystems and Processes

“Nobody owns the Bitcoin network much like no one owns the technology behind email. Bitcoin is controlled by all Bitcoin users around the world.” — Bitcoin.org

Bitcoin’s governance process can be summarized as off-chain governance with no centralized foundation.

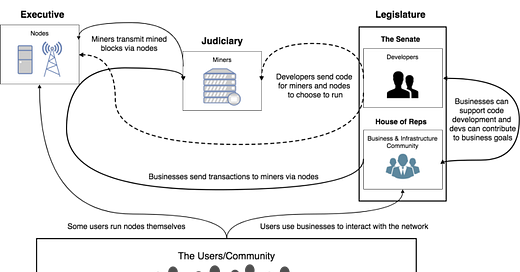

One useful way to conceptualize Bitcoin governance is as a system based on checks and balances, somewhat analogous to the US government.

Bitcoin core developers legislate by proposing software changes in the form of Bitcoin Improvement Proposals. Bitcoin miners who maintain the infrastructure that processes the transactions judge the validity of those changes and decide whether or not to adopt them. Bitcoin node operators have executive veto power which can be exercised by refusing to run a software version which aligns with the one used by the miners. Bitcoin users are the citizenry, who hold the ultimate power to revolt by abandoning software they don’t like, effectively rendering the system useless.

Economic incentives are the glue that holds the system together, ensuring that it is in the best interest of all parties to maintain the integrity of the system. If the miners or developers alienate the users, their tokens will also decrease in value.

This is a useful analogy for the purposes of this piece, but it is imperfect. While Bitcoin governance can be usefully compared to constitutional, corporate, and internet governance, it possesses unique features, such as the capacity for users to fork the software and create their own blockchain, that distinguish it from these other models.

“The possibility of forking means that unlike many other ways to resolve societal collective action problems, including a reliance on coercion, Bitcoin governance is based on deliberation, persuasion, volition, and choice.” — Bitcoin Governance as Decentralized Financial Market Infrastructure

Bitcoin’s Civil War

In 2015, Bitcoin faced an existential crisis. The Guardian newspaper proclaimed that “bitcoin was facing a civil war.”

The core issue being debated was “how should Bitcoin be scaled?” As bitcoin had grown from a niche experiment into a system with signs of meaningful adoption, users were faced with increasingly high transaction fees and slower processing times. The two belligerents in The Blocksize War were the Big Blockers and the Small Blockers.

Big blockers advocated for modifying Bitcoin to increase the 1MB block size limit specified in Satoshi’s original code through a hard fork. They believed this was necessary to ensure Bitcoin could grow into a payment network with the capacity to rival the likes of Paypal or Visa.

Small Blockers fought to maintain the original 1MB size limit. They were concerned that increasing the block limit would make it too expensive for individual users to run Bitcoin nodes. This would leave large companies as the only actors capable of hosting nodes, thus compromising the network’s decentralization and security.

The debate dragged on until 2017, culminating in a “user-activated soft fork” which embraced a proposal from the Small Blockers. The block size limit was modestly raised to 2MB and the groundwork was laid for “second-layer” scaling solutions such as the Lightning Network. Dissenters forked off into their own network, “Bitcoin Classic”. The fate of the system was decided by the users.

This saga illustrates how Bitcoin’s highly informal governance process leads to situations in which governance debates are carried out in a messy, prolonged fashion because there is no formal framework for resolving internal disputes. The fact that it’s hard to make significant modifications to Bitcoin increases its resilience, but also hampers its capacity to adapt to changing circumstances.

“The block size debate is a good illustration of this tendency. Although the debate was framed as a value-neutral technical discussion, most of the arguments in favour or against increasing the size of a block were, in fact, part of a hidden political debate.

Indeed, except for the few arguments concerning the need to preserve the security of the system, most of the arguments that animated the discussion were, ultimately, concerned with the socio-political implications of such a technical choice (e.g. supporting a larger amount of financial transactions versus preserving the decentralised nature of the network). Yet, insofar as the problem was presented as if it involved only rational and technical choices, the political dimensions which these choices might involve were not publicly acknowledged." — The invisible politics of Bitcoin: governance crisis of a decentralised infrastructure

Ethereum’s Benevolent Dictatorship

“No one person owns or controls the Ethereum protocol, but decisions still need to be made about implementing changes to best ensure the longevity and prosperity of the network. This lack of ownership makes traditional organizational governance an incompatible solution.” — Ethereum.org

Ethereum’s approach to governance can be summed up as off-chain governance steered (but not controlled) by a benevolent dictator and centralized foundation.

Subsystems and Processes

Ethereum’s governance process is very similar to Bitcoin’s. Core developers propose software changes with Ethereum Improvement Proposals. Validators (Ethereum’s equivalent of Bitcoin miners) can decide whether or not to adopt those changes. Node operators run software, and users hold ultimate veto power.

One of the most significant differences is that Ethereum’s creator, Vitalik Buterin, is a well-known public figure who remains active in protocol governance. Whereas we still don’t know who Satoshi Nakamoto (publisher of the Bitcoin whitepaper) is, and their last public message was on December 12, 2010.

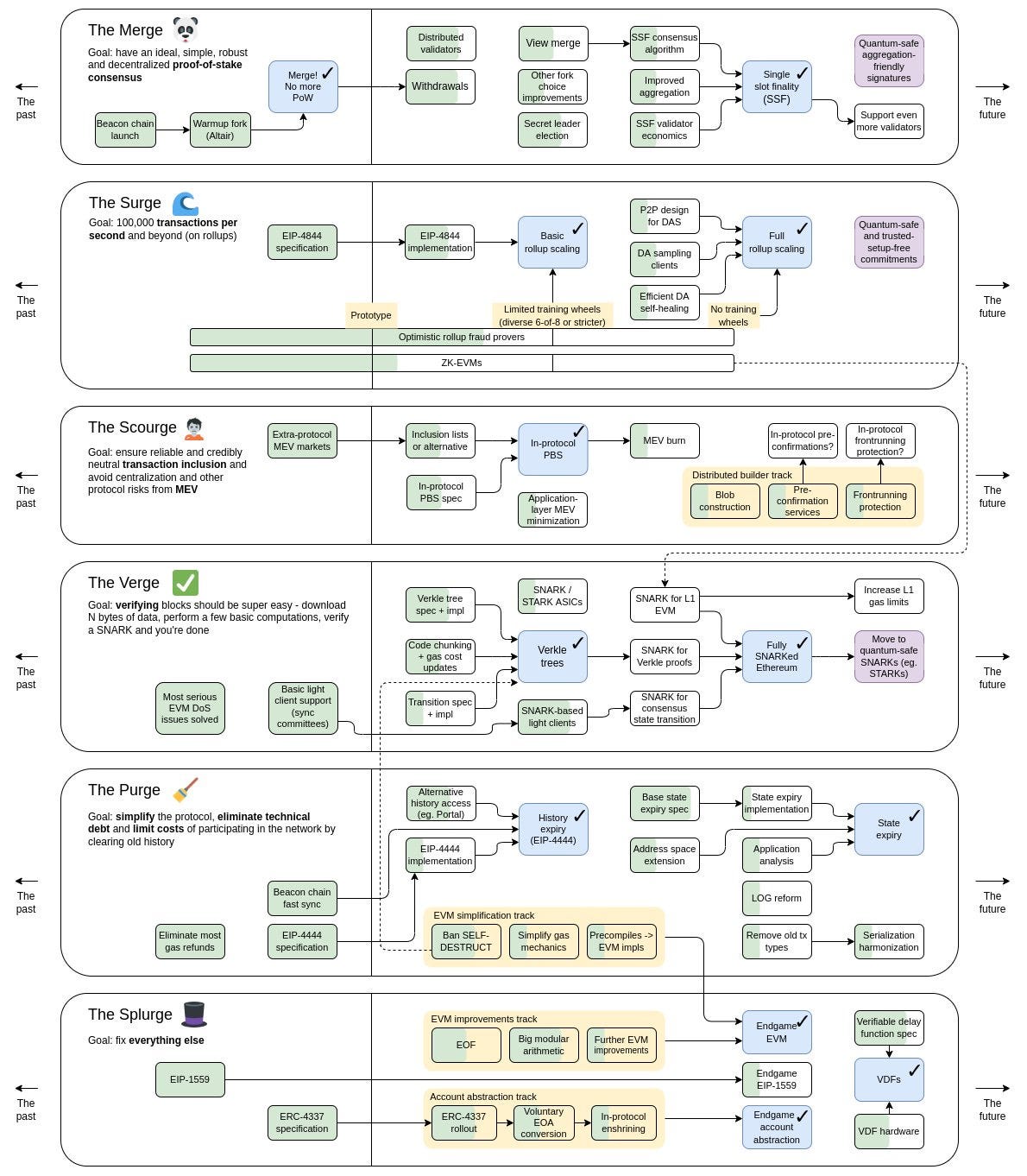

Last December, Buterin published a detailed long-term roadmap that dictates the direction for Ethereum’s future upgrades. It will be followed in large part because the community trusts Buterin and depends upon him for technical vision and leadership. He can’t force anyone to adopt the changes, but the community tends to listen to him. Bitcoin lacks such a singularly powerful and active figurehead.

The DAO Fork

A crisis that took place early in Ethereum’s history demonstrates how having strong leaders stewarding blockchain development can influence governance.

In 2016, an attacker discovered an exploit in a smart contract for The DAO which allowed them to drain 3.6 million ETH (~$60 million.) The DAO had raised more than $150 million from more than 11,000 investors and its contracts held approximately 14% of all circulating ETH.

Developers at The Ethereum Foundation proposed a hard fork which would roll back Ethereum’s network history to before the attack, and reallocate The DAO’s Ether to a new smart contract where investors could withdraw their funds.

This was controversial because blockchains are supposed to be immutable and censorship resistant. There were no issues with Ethereum at the protocol level and the attacker hadn’t broken the rules of The DAO’s smart contract. The developers who wrote the contract simply had not anticipated it could be used in that way. To roll back the chain in response to someone obeying the rules of the system was perceived by some as against the ideals of blockchain technology.

The majority of stakeholders chose to adopt the change and the fork was implemented. However, a minority of users refused to accept the fork and continued supporting the old chain, which is now known as Ethereum Classic.

The DAO hack helps to illustrate how central, trusted figures within the Ethereum ecosystem wield the power to propose significant changes in times of crises and have their suggestions be accepted voluntarily by the community. Unlike Bitcoin’s messy civil war which dragged on for years, Ethereum swiftly resolved its first major crisis within weeks. However, it could be argued that Ethereum sacrifices some degree of stability and predictability in order to achieve greater capacity for rapid innovation and adaptation.

“Practically speaking, I'm a large part of the story for why the platform will get better of the next few years," Buterin said…"My short-term goal is to shift the story to, 'the protocol will succeed because of myself, plus all of these other people who are capable of moving things forward.'” — Ethereum's Boy King Is Thinking About Giving Up the Mantle

“Least proud moment? Definitely the handling of the DAO fork situation. A lot of people did feel betrayed as a result of the DAO fork. A lot of people did feel like their expectations got violated. And a lot of people felt like their opinion was disrespected, especially people who opposed the fork.” — Vitalik: Ethereum, Part 2

Cosmos’ Decentralized Political Economy

"Cosmos blockchains come prepackaged with a governance system — a decentralized process for making decisions. — State of Cosmos Governance 2021

The Cosmos governance process can be summed up as hybrid on-chain/off-chain governance with several leaders and foundations coordinating to steer development.

Subsystems and Processes

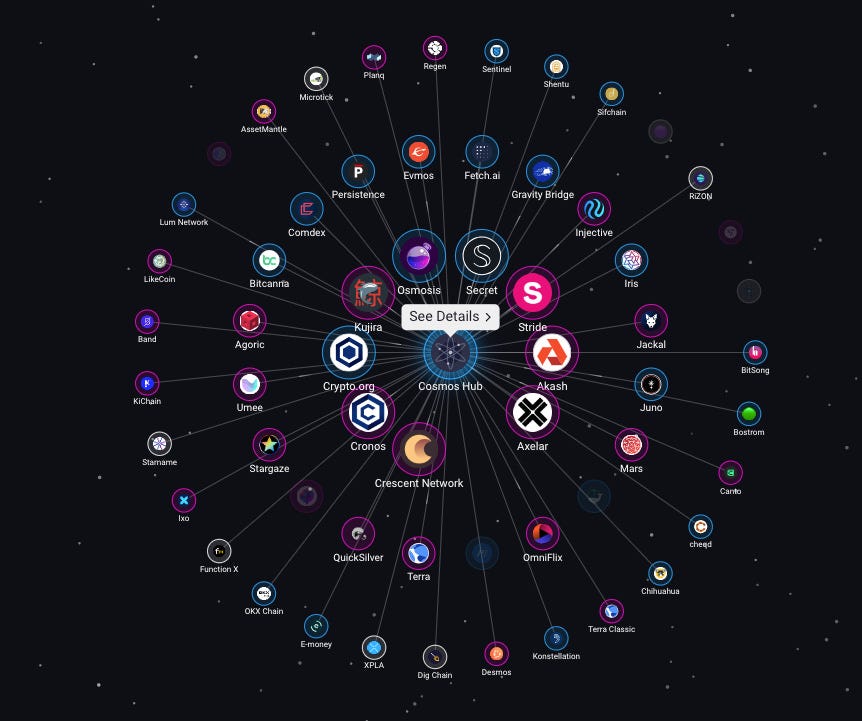

The Cosmos Hub is a blockchain which sits at the center of an “internet of blockchains,” the Interchain. Its native cryptoasset is called ATOM. Each blockchain in the Cosmos Network is built using the Cosmos “design framework for building blockchains.” Each chain maintains its individual sovereignty while benefiting from the ability to communicate with other chains.

This architecture is significantly different from that of Bitcoin and Ethereum. Decentralized and seamless communication between Bitcoin, Ethereum, and most other blockchains is difficult because they operate under different technical rules. The Cosmos vision is one of “an ever-expanding ecosystem of interconnected, blockchain-based apps and services” that can easily talk to each other because they are based on the same protocol.

Cosmos Hub developers sponsored by foundations like Informal Systems and the InterChain Foundation create Cosmos Improvement Proposals. Validators secure the network, and node operators run software. But that’s about where its similarities with Bitcoin and Ethereum end.

Cosmos Hub eagerly embraces on-chain governance to enact protocol level changes. ATOM token holders wield power in the form of the ability to submit proposals which are voted on by validators and delegators, committed to the blockchain, and enacted by validators.

Code-based proposals are used to suggest changes to technical, on-chain parameters, such as the number of active validators. Text-based proposals are used to do things like request funds, tackle security issues, and agree upon governance principles.

The Veto of Cosmos 2.0

In November of 2022 the Cosmos Hub community voted on the text-based Proposal #82, a referendum on a new Cosmos White Paper which outlined an ambitious new vision for the future of the Cosmos Hub that would secure its role as the key driver of growth and collaboration within the broader Cosmos ecosystem.

Under the proposed plan, any Cosmos-based chain would be able to “borrow” security from the main Cosmos hub, ATOM holders would gain new and more convenient ways of earning interest on their holdings, and a “Cosmos Assembly” would be formed, accountable to ATOM holders and managing the Cosmos Hub.

Lively discussion about the proposal took place on the governance forums, in interviews with media outlets, and on Twitter.

Ultimately proposal #82 was rejected. One Cosmos co-founder felt the proposal contained major risks. Some community members argued that the proposal was too broad, and that each piece of content mentioned in the whitepaper should be voted on in separate proposals.

After the defeat of prop #82, it appears that the “piecemeal” approach to incorporating individual elements of the original proposal is exactly what’s playing out. This March, proposal #187, which narrowly focused on allowing the Cosmos Hub to provide security to other chains in the Cosmos network, was passed with 95% in favor.

Observing how the Cosmos Hub community makes on-chain governance decisions in a highly participatory manner gives us insight into what it looks like when public blockchain infrastructure is governed in a way that resembles direct democracy, rather than the representative variants found in Bitcoin and Ethereum.

Cosmos gives users in its ecosystem enormous amounts of sovereignty at the expense of not allowing founders to push through swift, sweeping changes. Cosmos founder Ethan Buchman instead embraces the messy reality of deliberative politics as a key feature of the system.

“At the heart of Cosmos are the principles of sovereignty and interoperability — the right for communities to be sovereign over their own infrastructure and applications, and for sovereign communities to be able to peacefully interoperate with one another.”

“The lack of a singular centralized company led by a singular figurehead means decision-making can be more complex — but it can also be more representative and robust.” — The Mind, Body, and Soul of Cosmos.

Without an integrated governance structure, Bitcoin developers and users must fight battles of opinion out on public forums like twitter, leaving the system stable but slow to innovate. Comparatively, Ethereum's network is more dynamic with greater capacity to react and adapt in relation to external pressures. Cosmos opts for internalizing these political pressures as a driving force of the system, enabling users to constantly improve and modify their own ecosystem.

Public blockchains, DAOs, and on-chain organizations are all part of a vast, global “laboratory for democratic governance that interweaves civic and corporate governance traditions in a way previously impossible.”

Coinbase co-founder Fred Ehrsam wrote in 2017 that “we are currently in the primordial ooze phase of blockchain governance.” I would argue that we are now in the era of complex life emerging, with multi-cellular organisms cooperating and competing in a rapidly growing evolutionary landscape.