Last week I covered Mobus and Kalton’s first principle of systems science. This principle states that everything in the observable universe can be understood as a system.

The second principle states that all systems are processes organized as hierarchies.

This article will define these terms and explain the utility in viewing systems through the lens of process and hierarchy. The human brain and political systems will then be used as examples to illustrate how these concepts apply to two different types of systems we are all familiar with.

Process

A process can be defined as something that takes inputs and does work on them to produce outputs. Any system can be viewed as a process which unfolds over time.

This is important because viewing systems as processes helps us see them as things which do work on materials over time. They are not static and unchanging, but dynamic and constantly reacting to their environment. Systems must do work and consume material to maintain their systemness (the quality of being a system). Their work results in the production of outputs which flow back into the environment.

Even something seemingly stable, like a rock, can also be understood as a process. A rock sitting at the bottom of a turbulent stream will take raw material, such as water which seeps through its cracks, and energy from changes in environmental temperature as inputs. These flows and fluctuations cause the rock’s component molecules and crystals to change. Over time, it will shed flakes such as silica, which are then output back into the surrounding environment in the form of sands and clays.

Hierarchy

A hierarchy can be defined as a layered structure in which the lowest layer is made up of the simplest components in the structure. Hierarchies are often represented by branching tree diagrams, like the one below. The system of interest sits at the highest level of the hierarchy, and is composed of subsystems which are then represented in the lower levels.

Viewing a system as a hierarchy is helpful because it helps us understand how it is organized. It provides a clear picture of how subsystems are related to one another and how flows such as power and information spread throughout the system.

People often associate the word hierarchy with top-down control, unfair distribution of power, or oppression. But the truth is that hierarchies are a natural phenomena which emerge as a consequence of self-organization. Hierarchical arrangements allow systems to effectively manage various functions and outputs as they contend with increasing degrees of complexity.

To illustrate these concepts more concretely, I will apply them to the analysis of two types of real world systems: the human brain and political process. They are both very complex, and the descriptions below are only meant to give a glimpse into how a systems approach can be applied to understanding them. More comprehensive and detailed analysis of both can be found in Principles of Systems Science and Systems Science: Theory, Analysis, Modeling, and Design, the two textbooks which are acting as the primary foundation for this series.

Brains

The Brain as Process

The human brain is an organic system. It is a complex process that is constantly doing work during both our waking and sleeping hours.

Your brain uses sensory receptors, like the eye, to receive inputs, like a ray of light. For example, a red ray of light at a traffic signal means you should stop your car. The brain receives this input and then does work on it by processing and interpreting it so you can react appropriately. After integrating this information, your brain generates an output, such as stomping your foot down on the gas pedal which will bring the car to a standstill. The brain then moves on to processing new sensory inputs from the environment so you can decide what action to take next.

The Brain as Hierarchy

The human brain is one of the most complex systems in the universe. Seeing it as a process helps us understand what it does. But how is it organized?

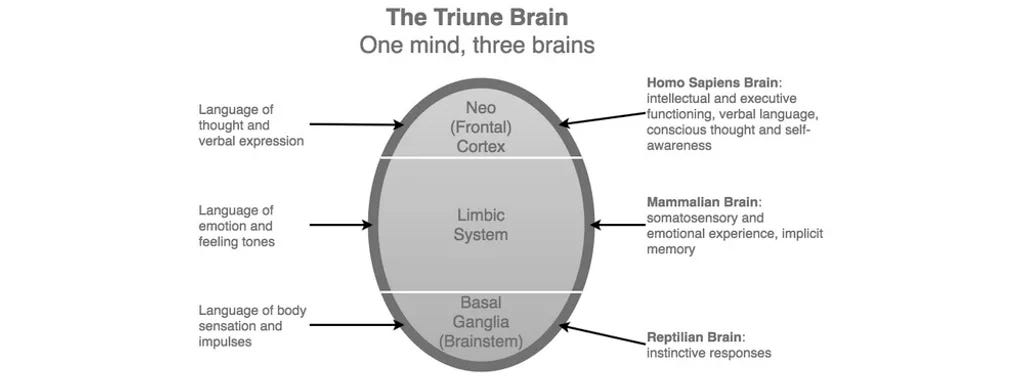

The work done by the brain is divided into several different parts. It can be viewed as a hierarchy composed of three primary subsystems: the brain stem, the limbic system, and the neocortex.

The brainstem controls basic body processes like breathing and the rate at which your heart pumps. The limbic system handles memory storage and retrieval and establishes emotional states. It also helps link the unconscious functions of the brainstem with the conscious functions of the neocortex. The neocortex is the largest and most complex part of the brain, responsible for the exceptional strategic thinking abilities of humans. It allows us to create new technologies and make plans that extend years or decades into the future.

This hierarchy of subsystems evolved over millennia to help us grapple with, adjust to, and shape an increasingly complex world.

Political Systems

Political Systems as Processes

Political systems are social systems. We are all embedded in some sort of political system which largely dictates the rules we must follow and helps shape the society we are a part of.

Viewing a political system as a process can help us understand how it maintains itself over time. David Easton was a political scientist who was heavily inspired by early work in general systems theory and cybernetics. Easton modeled the political system as a process whose primary function is to turn demands and support into decisions and policies that will be widely accepted by society as legitimate.

We can use this model to see how the U.S. political system does work to deal with the top policy issue for 75% of Americans—strengthening the economy.

The shared desire for the vague concept of a “stronger economy” manifests in a number of specific demands being made of the political system. Citizens ask for higher or lower taxes, more or less regulations, more and better jobs, and lower inflation. Demand acts as a signal to the political system. It tells the politicians what sort of work they should focus on. Demand plus support is the necessary driver of any political system. Governments require support in order to survive. This can come in the form of paying taxes, voting, or obeying the law.

The political system does work in order to satisfy the various desires of the citizenry. Members of Congress debate legislation, regulatory agencies craft regulations, and the Federal Reserve deliberates over where to set interest rates. The system produces outputs in the form of policies which are designed to address demands and ensure ongoing support. Bills such as The Inflation Reduction act are passed and enshrined into law, executive orders focused on promoting competition are issued by the President, and the Federal Reserve raises interest rates in an effort to combat inflation.

These decisions feed back into the environment and have meaningful consequences for the livelihood of Americans. They create new circumstances, such as higher interest rates leading to bank failures which put people at risk of losing access to their money. Citizens then respond by making new demands and re-assessing their level of support for the system. Thus, the political system is an ongoing cyclical process that continues to exist only for as long as it can maintain a viable level of support.

Political Systems as Hierarchies

Thinking about the American political system as a process helps us conceptualize how it turns demands from citizens into concrete policies over time. Viewing it as a hierarchy causes us to see the various subsystems it is composed of and how they interact with one another.

At the top of the hierarchy we have three very large systems—the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. Each one of these is made up of smaller subsystems like the Senate, The Cabinet, and the Supreme Court.

As the federal government has taken on an increasing amount of power and responsibility since its founding, it has grown into a sprawling bureaucratic hierarchy with multiple layers. New subsystems emerge in order to help the government deal with increasing amounts of complexity that have arisen as the population has grown and the country has turned into a global superpower.

People tend to focus on personalities when discussing American politics. They act as if the President is “in charge” and should be credited with all of the nation's successes and blamed for all of its failures. Or they focus on the behavior of prominent figures in Congress or members of the Supreme Court.

Taking a systems approach makes it clear that this focus is misguided. Personalities are important, but they are not the political system. Institutions, processes, and connections between subsystems are just as, if not more important than the individuals who happen to be within a certain government role at a particular time.

At the widest level of analysis, the Constitution is the ultimate system of interest. Without a shared belief that the Constitution is the law of the land and the structures and processes it outlines are legitimate, there would be nothing to hold the rest of the political system together.

Process and hierarchy are essential concepts for helping us reason about the work that systems do and the ways in which they organize themselves to accomplish their goals.

Next week we’ll look at Principle #3 of systems science, which states that all systems can be understood as networks.

Prompts and questions for reflection:

Describe the organization you work for as a process. What are its inputs? What sort of work does it do? What are its key outputs?

Describe the organization you work for as a hierarchy. Does the organization run smoothly? If not, on what layers do you see problems emerging? Would it benefit from more information flowing from the bottom-up, or more top-down control?

Choose an important social system you think is broken. Why is it not functioning as a process? What sort of changes in the hierarchy might you suggest to improve its functioning?