Best of System Explorers: Part One

As we approach the end of the year, I felt it would be nice to look back and highlight some of my favorite pieces of writing since starting this journey in April.

I’ll share three pieces today and three more next week.

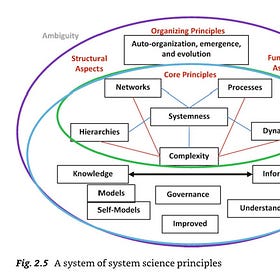

In Systemness I introduced the notion that we can find scientific principles which apply to all systems, regardless of their type. I outlined George Mobus’ proposed 12 principles of systems science which served as the basis for a series I developed over several months. While the series wasn’t quite as cohesive as I imagined it would be, the process of writing and completing it was incredibly educational and satisfying.

Systemness

Over the next few months I’ll be introducing one new principle of systems science per week. These principles were identified and defined by George Mobus and Michael Kalton in their introductory textbook Principles of Systems Science. Before diving into the first principle, let’s talk briefly about what scientific principles are and why we need them.

In Systems Science and Artificial Intelligence, I took time to introspect and assess my relationship to LLMs like ChatGPT. Doing so inspired me to sketch out the rough outlines of a personal vision for how a systems approach might empower humanity to develop AI in a way that is more likely to serve us.

Writing the piece also led to concrete changes in my behavior. Rather than avoiding ChatGPT, I started exploring what it meant to use it in a measured way and use the experience to inform my thinking on what better AI systems might look like.

Systems Science and Artificial Intelligence

“The saddest aspect of life right now is that science gathers knowledge faster than society gathers wisdom.” — Isaac Asimov Recent events have forced me to re-evaluate my relationship to the topic of Artificial Intelligence (AI). Daniel Friedman, head of education at the International Society for the Systems Sciences (ISSS) held an

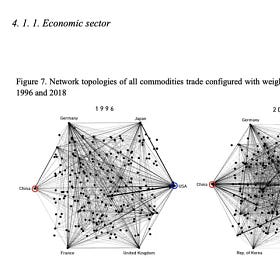

In Complex Webs of Power, I summarized key findings from one of my favorite papers in network science. The paper explores how the methods of network science can help us get a more nuanced and holistic perspective on important geopolitical issues (in this case global hegemony in the 21st century) that isn’t attainable by relying on traditional reductionist methods.

Complex Webs of Power

Will the United States maintain its spot as the world’s dominant superpower during the 21st century, or will it be displaced by China? Perhaps we are slowly entering a multi-polar world order filled with several competing powers and no clear leader?

(Note: it looks like the paper has recently been removed from SSRN. Please email me if you’d like a copy.)